MY VISIT TO ULHASNAGAR

By Jaya Kamlani

You must be the change you wish to see in this world. – Mahatma Gandhi

On November 28, 2005, I received this email:

“Demolitions of the properties of Sindhis have started on a massive scale in Ulhasnagar, near Mumbai, in the state of Maharashtra. At least 855 buildings will be demolished throwing out more than one lakh (100,000) Sindhis on the roads because there are no plans for rehabilitating them. Only the Sindhis have been singled out for such a ruthless treatment by any state government in the whole of India….”

So why did I come to the defense of the residents of Ulhasnagar?

Surely there must have been an astral link at the time, for I, who had been living in the United States of America for almost forty years, somehow connected with the disenfranchised people half a world away in Ulhasnagar.

Besides, I was born in the same month and year of the partition – August 1947 – on the other side of the border in Hyderabad, Sindh, and was only a one-week old infant when my family had to flee our homeland. For a year, we hopscotched through several states of India until we settled in Bombay (Mumbai). There, for a year, my family and I lived in the crammed army barracks of World War II in Koliwada-Sion, until we found a comfortable home in the suburban town of Mahim, where I lived for almost twenty years until I left for America in early 1969. During my childhood years, I had heard about the hardworking residents of Ulhasnagar and the small businesses that thrived there. My mother used to buy paapads, khichaas and kacharis from the women of Kalyan and Ulhasnagar who showed up at our door with homemade snacks.

When I received the email about the mass demolitions in Ulhasnagar, I felt as if my own home was being torn down. It could very well have been my family and I who had settled in the refugee camp of Ulhasnagar after the partition of India.

Not since the partition of 1947 that split the country into India and Pakistan had the Sindhi-Hindu community come together in solidarity until news of the Ulhasnagar demolitions took the community by storm. The partition had driven the Sindhis out of their homeland, as Sindh province came under the jurisdiction of Pakistan, and Sindhis became refugees in their own country – India. Many settled in Ajmer, Jodhpur or Mumbai, while others sailed for distant shores. Still others settled in Ulhasnagar and Kalyan on the outskirts of Mumbai.

Ulhasnagar, a refugee camp inundated with World War II army barracks, has since mushroomed into an un-planned community. Alas, today it is plagued by structures that do not meet the city's standard building code. It is a city that grew vertically due to its geographical limitations. But whose fault was it that five and six story buildings sprung up when they were limited to four, or that structures were erected close to storm drains? Surely not that of the residents who had paid taxes all these years. What about the city officials who had approved the building plans in the first place, or closed their eyes to the illegal structures that went up?

No, there was more to it than non-adherence to building codes that called for the demolitions. This was gentrification, which the dictionary describes as “the process of renewal and rebuilding accompanying the influx of middle-class or affluent people into deteriorating areas that often displaces earlier usually poorer residents.” In other words, the state government needed land for industrial centres, modern high-rise buildings, malls and highways. The state was willing to throw out the refugees of partition and their families to make room for new development. To displace them again would be grave injustice.

Without wasting any time, I shot off letters to the Human Rights Watch in Washington D.C and New York, giving them a background of Ulhasnagar, requesting them to follow up with the Human Rights Commission in Mumbai, and urging them to do everything they could to prevent the mass demolitions. I contacted my Sindhi friends worldwide and the South Asian Journalists Association (SAJA) in New York, of which I am a long-time member, and kept everyone periodically updated on the situation.

But where were our Sindhi leaders, the mega developers and our religious organizations when we needed them most? Why didn't they rise to the occasion and give a helping hand to our brethren of Ulhasnagar to whom fate had not been so kind? In contrast, during such times in America, I have found that the religious organizations do not only provide solace to the suffering; they also provide food, clothing, shelter and financial aid to the needy.

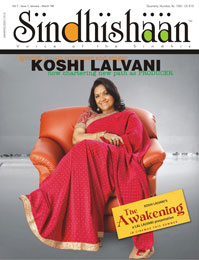

This winter, while visiting the villages and shantytowns of India to do field research for a book I am working on the rural life and the people left behind during the economic surge of India, I thought to myself, what better place to start my mission than Ulhasnagar? I asked Ranjit Butani, publisher and editor of this magazine, to arrange the tour. On a Sunday morning on December 2, 2007, during my visit to Mumbai, six of us drove to Ulhasnagar: Ranjit Butani, Vijay Kewalramani, Professor Baldev Matlani, Koshi Lalvani of Dubai, my friend from U.S – Dr. Asha Rijhsinghani, and myself. It was a couple of hours drive to Ulhasnagar. Along the way, Koshi sang for us “Jaag Sindhi Jaag” – the theme song of her movie “The Awakening”. My ears tuned into her melodic voice and the inspiring lyrics.

Around noon, our SUV pulled up on a side street. There in front of us stood the skeletal remains of the five-story Rani Maa building, one of the three buildings bulldozed during the court-ordered demolitions in December 2005. With its balconies stripped down, the dilapidated walls of the ruins stared down at us.

Driving down narrow alleys that wove around a town stacked with weather-beaten structures, we came upon a freshly painted pink three-story building named Laxmi Ganga Niwas. Ranjit explained that the building had been eighty-percent demolished and the owners had rebuilt it with their own savings and from donations received from philanthropists. This time, the structure was rebuilt with city approval.

We walked up a flight of stairs and were welcomed with open arms by Mrs. Narang, the matriarch of the family. She sat us down in the drawing room, introduced us to her children and grandchildren, who hugged us, touched our feet for blessings, and served us snacks and sweets. I was overcome by their warmth, hospitality and outpouring of love. It was such a delight to see three generations of a family living under one roof, like the joint families of Sindh who held on to traditional values.

Teary-eyed, Mrs. Narang recounted the week they received the eviction notice from the city. A couple of days later, her husband had suffered a fatal heart attack. This was the only home he had known since the 1947 partition of India. Brushing away the tears, the matriarch wished her husband were around to see them settled in their new home. My heart melted for her.

Like Mrs. Narang and her family, nineteen other families were displaced during the demolitions. None of them received any compensation from the city. They survived the ordeal with help from family and friends. Eventually, MP Ram Jethmalani won the court case for the people of Ulhasnagar before tens of thousands more families were put out on the streets.

We lunched with Baldev Matlani's brother's family over an interesting conversation of the partition days, Sindhi freedom fighters and the Indian Congress leaders of the time, then stopped by the Gaushala at the Community Centre, where we fed hay and carrots to the ailing cows brought from neighboring villages and nourished here to provide milk for the residents of Ulhasnagar. We met with Swami Dev Prakash Maharaj – the guru of Ulhasnagar, and with Dr. Dayal Asha – custodian and founder of Janta Janardhan Parishad, the home for the elderly.

At the senior citizens home, while elderly women chanted bhajans in the temple, men lazed alone in their bedrooms, or in chairs outside their rooms. The bedrooms were crammed – three narrow beds to every room, one bed too many for comfort. No music was heard in the corridors. The courtyard, too, looked dreary. The women appeared to have found an outlet, but the men waited for their final sunset. The elderly wilted away like the lifeless flowering shrubs in their yard… A spruced up colourful garden could brighten their day. A bingo (housie) game in the community room could bring cheer to their last years.

During my two-and-half month journey through the villages and slums of India this winter, I visited another Gaushala run on an industrial scale by a research institute that holds farm and livestock training programs on its premises. There I learned about the different breeds of cows, which ones provide better milk and which ones are better suited for plowing of fields, and about crossbreeding and artificial insemination techniques used to improve livestock yield. The institute is currently involved in a research project to determine if a certain type of fodder fed to the cows could enhance milk production.

That afternoon we pulled up by a foul-smelling contaminated canal – an open sewer that ran between the buildings and through the town, the stench of which made me sick to my stomach. Standing there pinching our noses, we wondered how the residents of Ulhasnagar survived day after day in such filth. A dog stood in the midst of the shallow sewer looking in our direction. When it would step out of the slimy green and brown muck and wander down the alleys, it would leave a trail of bacteria. Children may even pet it unaware that it is the carrier of diseases.

Two years ago, Ulhasnagar, “City of Joy” crammed with shoddily built structures and no city sanitation services, was to be brought down brick-by-brick, one building at a time. Even today, the city lacks a modern sewer system. Waste runs through the streets in open channels, exposing residents to a deep pervading stench, and risks spreading bacteria and viruses to people who routinely walk, or bike through the streets. Monsoons can wreak havoc as the sewage overspills and children wade through the infected flooded streets. The sanitation system is a major health hazard to the people of Ulhasnagar. It cries for urgent attention.

The city department's purpose to tear down the buildings was not because they did not meet the city's standard building code, or for the sake of public safety, but rather to replace them with modern buildings that would appeal to the growing population of the city's wealthier residents who could pay higher rents and taxes. Only twenty miles down the road stand tall corporate structures of Cadbury, J.K.Chemicals, Raymonds, Voltas, Glaxo, Cadila Healthcare, Hindustan Forging, and others.

Forty miles down on Bandra-Kurla Road, in the heart of Mumbai, are located Lupin Laboratories, Bank of Baroda, Bank of India, State Bank of India, Tata Consultancy Services, Reliance Industries, UTI, ICICI Bank, Suzlon, National Stock Exchange, Bharat Diamond Bourse, as well as towering American corporate structures of steel and glass such as Intel, Citicorp, Cisco, Motorola and IBM.

The internet age has revolutionized India. Salaries for those with advanced degrees in science and technology have doubled and tripled in a couple of years, yet many are left behind in this booming economy, such as the people of Ulhasnagar.

India is a “land of paradoxes,” where the rich and poor live side-by-side, yet in different worlds. On the one hand, there are prosperous Sindhi developers who have built skyscrapers with modern amenities in major cities of India. On the other hand, we have people living in deplorable conditions in Ulhasnagar and Kalyan.

Sometimes we wonder what can one person do in any given situation? But if each of us did our little part, we could make this world a better place for all.

Now that the demolitions have come to a halt and the buildings are in the process of being regularized by the city, will our Sindhi philanthropists and developers such as Hiranandani, Raheja, Geras, Ahuja, Evershine rise to the occasion, work with the city engineers and take on the challenges of Ulhasnagar, Kalyan and Pimpri? Will Swami Shanti Prakash Ashram Trust of Ulhasnagar and other Sindhi religious and non-profit organizations stand up for the hardships of the communities they represent?

However, my travels through the villages and city slums of India revealed that charitable handouts do not work, and no project can be successful unless there is participation or vested interest from the community. The local people who stand to benefit from the program must share the burden. Their contribution should be no less than 25 – 30% of the total labor or cost of the project. Without community involvement, the project is doomed for failure.

Our communities could also work with credible NGOs (non-government organizations) and NPOs (non-profit organizations) with proven successful track records, and find solutions to sanitation services, education, vocational training, healthcare and other issues.

(Jaya Kamlani is a writer and former IT/Management Consultant living in Atlanta, USA. )