INDIAN NATIONAL ANTHEM A DEVOTIONAL HYMN

- by Karan Makhija

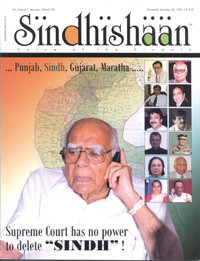

Recently, the Supreme Court was moved, thought a Public Interest Litigation (PIL), with a request to make a change in the National Anthem of India. The suggested correction was to have the word ‘Sindh’ removed from the anthem.

The litigant, one Sanjeev Bhatnagar, argued that the province of Sindh was not longer a part of India. Instead, a region like Kashmir could be added to the anthem. He added that inclusion of the word ‘Sindh’ in the anthem violates the sovereignty of Pakistan and hurts the sentiments of one hundred crore Indians. The Supreme Court has considered this PIL seriously.

To understand in full, the implications of the proposed change one must understand, at least in part, the ideas that are India, Sindh, and indeed the anthem itself.

The national anthem was adopted by the Constituent Assembly in the presence of national leaders on January 24, 1950 despite all of them being aware of the fact that Sindh was part of Pakistan. It was written, and first sung, in 1911. In translation, it read like this :

Thou art the ruler of the minds of all people

Dispenser of India’s destiny

Thy name rouses the hearts of

Punjab, Sindh, Gujarat and Maratha,

Of the Dravida and Orissa and Bengal;

It echoes in the hills of the Vindhyas and Himalayas,

Mingles in the music of Jamuna and Ganges and is

Chanted by the waves of the Indian Sea.

They pray for thy blessings and sing thy praise,

The saving of all people waits in thy hand,

Thou dispenser of India’s destiny.

Victory, victory, victory to thee.

Since the Song was used by the Congress to welcome King George V to India, a controversy has arisen about whether we are still singing the praises of a foreign monarch in our anthem.

This misconception needs to be cleared. Tagore himself has completely debunked the idea that he ever wrote this in praise of the King. The circumstances of the events and the ensuing newspaper reporting gave rise to this controversy.

“ . . . Since Tagore did not immediately refute the allegation, the perception spread that the song was a eulogy to the monarchy . . . .In a letter to Pulin Behari Sent, Tagore later wrote, “a certain high official in His Majesty’s service, who was also my friend, had requested that I write a song of felicitation towards the Emperor . . . I pronounced the victory in Jana Gana Mana of that Bhagya Vidhata of India . . . . That Lord of Destiny . . . could never be George V, George VI, or any other George. Even my official friend understood this about the song. After all, even if his admiration for the crown was excessive, he was not lacking in simple common sense.” From PERSPECTIVE – ‘Singing the Nation’ by Nasreen Rehman.

There is no question of doubting Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore’s loyalty to his motherland. It would be preposterous to even consider that he could have conferred such titles as Bharat Bhagya Vidhata on an earthly monarch. Also, given his relationship with Nationalist bodies and the sheer volume of his nationalistic writing and art, and views on Indian Nationalism and his anti-British acts, the view can hardly be allowed credence. The misconception is clearly a function of the Congress using the poem to welcome the king. Mahatma Gandhi has called the anthem a devotional hymn.

The anthem is a symbol in the minds of Indians, of everything that the people of India wanted their nation to stand for, and achieve.

And symbols must be left to be themselves. Symbols are merely tools to shorten and solidify lines of communication and congeal ideas. Changing them achieves nothing. It borders on meaninglessness, redundancy and leads to rejection of the symbol as a whole.

Changing the anthem will make it vulnerable, open to interpretation and subject to rational and historical scrutiny. And history says much about Sindh and its relationship with India.

More than any other nation perhaps, the idea of India is welded to it’s past. Let’s take a look at the word itself – the name – India. For the West, the word has its origins in Greek texts in the B.C.

This word, tossed though Greek myths and flaunted by philosophers, was found traveling through time until the resurgence of European contact with Asia. The overbearing idea of India as much fabled land of infinite riches went a long way in establishing the stature of the land, in the minds of Europeans. The unification of the land as the Indian subcontinent under British rule, and subsequent partitions of the same, gives India and its closest neighbours their current geographical boundaries.

And the name has a second, parallel history. The vortex of the historical journey is the much misunderstood word, Hindu. It was the Persians, and other tribes in the Mesopotamian region, who used this word to refer to the people who inhabited the land in an around the plains of the river Sindhu (Indus), and to its east. Only, they could not, or had difficulty in, pronouncing Sindhu, and changed it to Hindu. This Hindu then became the Greek Indie, or India. So the very name – India – comes from Sindhu.

The Indus Valley or Saraswati-Sindhu Civilization flourished here. This was the largest, oldest and most advanced civilization of the ancient world. Its two principal cities, Mohanjodaro and Harappa have been discovered in this province. There are many recent studies which suggest that it was this very people who, upon the destruction of their lands, moved east, to the Ganga Valley and authored or helped to author, the Vedic Civilization.

The land has forever been the door to ‘India’. First contact of the peoples of the sub-continent with Egypt, Phoenicia, Mesopotamia, Central Asia and Greece in proto-historical eras happened through what is today Sindh. Trading cities and large ports, all developed here first. Anyone who came to India through the western land route got his first impression of India from Sindh. The first person to oppose the Arab invasion of northern India was a Sindhi King.

Of course, this is all ancient history. In recent times Sindh came into the limelight once again with its exclusion from the Indian Union. Although it had a very large Hindu population it was not partitioned like the Punjab, the reasons for which can be debated endlessly. What did occur, as in the case of the Punjab, was a migration of mammoth proportions. Since then, Sindhis have spread all over India, and indeed the world.

The exodus and scattering cost the Sindhi community dearly. Being adaptive (considering they have been at a continental crossroads for five thousand years) they took easily to new languages and cultures. But being uprooted form a homeland is not something eve this most resilient of people could deal with very easily.

Their new generation is now in danger of completely losing touch with the major Sindhi texts or scriptures, Sufi saints, the Guru Granth Sahib, the Sukhmani Sahib, all of which have sustained the essence of one of the most secular and accepting philosophies in India, incorporating all religions that met across the bridges of the Indus. Much of this has been forgotten.

What has not been forgotten by Sindhis is the cost of the exodus (and they are being forcefully reminded that they are still paying). A large population was made to give up all that they had built, and resettle in an inconsistent manner, so that some political leaders could be satisfied. They gave up their homes so that others could live in peace, and now their very mention in the anthem supposedly hurts all other Indians.

The outcome of these events could springboard a host of activities, both within the Sindhi community, and within the country.

The first response from influential Sindhis all over through the media has been that the community required issues to rejuvenate itself, and this was the perfect opportunity. Maybe it will have a positive impact on the community. Like Mr. Bhatnagar, there could be some elements even in the Sindhi community (as there are in all communities) who see their gain in making issues out of nothing.

Maybe Sindhis all over will need to make their presence felt and start learning their language and focus on their cultural heritage. They could harness the power of their diasporas and . . . .

On the other hand they could take the view that it doesn’t really matter. If the government approves and parliament is moved successfully to change the anthem, it doesn’t mean that they are not Indians anymore. It doesn’t mean they’ve lost seven thousand years of history and heritage. It’s just like having text books doctored. It doesn’t mean a thing, does it?

The politically insidious would have a field day with such a precedent being set. Even this claim would have got their minds ticking. That ticking would sound, at the very least, like this.

How come large parts of the country are not mentioned or included in the anthem? How come the entire south has been encapsulated in one word – Dravida? Will adding the name Kashmir resolve the Kashmir issue and magically make all of it part of India because our national anthem says it is so? What about the North-East? Are they supposed to be included in the word Banga? Is that not what their agitations are all about – identity?

And it doesn’t stop at what kind of public debate will become fair game. It would also rationalize a whole new set of demands. Then we move into the realm of what can be included in India and what we can live without, which might also be what Mr. Bhatnagar propounds as it is a logical consequence of his suggestion.

The next step would be articulating degrees of importance various regions and communities have in making up the idea of India. This is what is all boils down to. Somebody needs to fabricate an idea, dig up an issue and rouse the people because the nation is going through an identity crises.

What should we, in the preset, consider to be India and Indians? Does India consist of a number of people residing within a particular boundary? Our country has always considered itself to exist far beyond its borders, in the ‘Little India’s of metropolitan cities around the world, in Non-Resident Indian remittances back home and in Dual-Citizenship offers. It is funny that at a time when we are trying to reclaim our Diasporas we also allow petitions like this.

There has been an earlier attempt to replace the word Sindh in the national anthem. The matter was taken up by Shri Jairamdas Daoulatram, a long-serving Member of Parliament, with not one but two Prime Ministers. The correspondence between Shri Doulatram and Pandit Nehru, and subsequently Lal Bahadur Shastriji and V. P. Naik (then Chief Minister of Maharashtra) has been collated by Shri Ghanshyam J. Shivdasani. The following is evident from their correspondence.

In 1964, at a function for laying the foundation stone for a bridge in Thana (Maharashtra), in the presence of the Chief Minister, V. P. Naik, and the Defence Minister, Y. B. Chavan, a group of school children sang the anthem with ‘Andhra’ instead of the word ‘Sindh’. The children had been using a book which contained this ‘revision.’ The Chief Minister took prompt action to correct the situation.

As an appendix to the same collation, attached was the transcript of the question relating to the presence of Sindh in the national anthem, as taken up in Parliament. On 26 November, 1957, question no. 497 raised in Parliament regarding the National Anthem was whether the government had considered the proposal to omit the word ‘Sindh’ from the National Anthem. The government considered that there was not sufficient reason for interfering with the original version of the anthem as composed by the late Dr. Rabindranath Tagore.

Even the institution of Public Interest Litigation has been misused in this case. It was inducted in the system so that a gross violation of fundamental rights could be redressed. But how does the presence of the word Sindh in the anthem leave anyone bereft of their fundamental rights? Who is being hurt by its presence in the anthem?

There is a special place for the PIL in our Judiciary. It does not depend on the long bureaucratic procedures the law normally follows. A PIL can be sent to the Supreme Court on a mere post card. Since the Court has so empowered the citizens of India, we should also be made accountable for the misuse of this power. This is an obvious case in point. Such gross disrespect and misuse should call for judicial action against the litigant.

If this sort of petition has been tolerated why don’t we just open the floodgates? Can the institution of the Public Interest Litigation serve a better purpose? Let’s change everything to fit the whims of somebody’s idea of India. Suggestions marked ‘PIL’ are welcome at the Supreme Court.

Nobody stands to gain from the proposed change. At best, the sentiments of a community will be hurt and insult will be added to injury. At worst, this removal will result in scores of other demands being made. And like the demand for more states has suddenly become the flavour of the decade, the easiest way to whip up a storm will be to demand for inclusion in the anthem. It will arise from every region of the nation and from within every community. It is just an irreconcilable and self defeating exercise.

How can we even consider stooping to the level of changing somebody’s poetry for what is effectively a publicity stunt? If the change is made, which would be an ethical horror anyway, would one every say that the anthem has been authored by Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore? How would we frame it? ‘Adapted from’, or ‘Inspired by’?

At what point, according to which historian, of what origin, and what political leanings, will the speculation stop with? Will we change all our notions about our past and identity with the next big historical discovery?

Even if the Sindhis had remained in Pakistan, the word Sindh would have had a place in the Indian national anthem. The culture of Sindh does not belong only to the Sindhis. The history of Sindh certainly plays an important role in forming the concept of India. This history is not ours to won. Nor is it a matter of speculation. Fortunately, it is ours to keep. It is symbolic vestiges like the word Sindh in the national anthem that not only become the capsules that carry our past into our future, but also contain the hope that our fragmented subcontinent is too enmeshed not to achieve a lasting peace at some point.

About the author :

Karan Makhija has done his B.A. in History from St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai and takes a special interest in ancient India. He continues to pursue his interest in the History of Sindh, and the Sindhi language. He was part of a theatre company for four years and dabbled in radio, and is a voice over artist. He is currently doing a post-graduate diploma in Content Creation and Management at the School of Convergence, New Delhi. His paternal and maternal grandparents came over from Sindh to Mumbai during the period of partition.